Newcastle Disease

Introduction

First officially reported in 1926, Newcastle Disease (ND) has since become a significant threat to commercial poultry, including chickens, turkeys, quails, and pheasants, as well as hobby and zoo birds.

The disease was initially discovered in Indonesia in 1926 but is named after Newcastle-on-Tyne, England, where it was identified in 1927. It is also known by other names such as Ranikhet, pseudo-fowl pest, and avian pneumo-encephalitis.

Newcastle Disease is caused by an avian paramyxovirus of serotype 1 (APMV-1), which belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family. It affects both wild birds and domestic poultry, typically presenting as a respiratory disease. However, depression, nervous manifestations, or diarrhea may also be the primary clinical symptoms. The disease is officially regulated, and its velogenic form must be reported to the OIE (OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code). It also has a zoonotic aspect as initial exposure to infectious material can cause transient and benign conjunctivitis in humans upon close contact.

Newcastle Disease (ND) is a highly contagious disease with symptoms that vary widely in type and severity. It poses a significant barrier to the international trade of poultry and poultry products, leading to substantial economic impact.

ND is a notifiable disease to the World Animal Health Organization (OIE). A global risk analysis can be conducted to distinguish between high challenge countries, where ND outbreaks are frequent, and low challenge countries.

In high challenge countries, when industrial chickens experience an ND outbreak, they often display high morbidity, high mortality (up to 100%), listlessness, dyspnea, and diarrhea. Nervous signs such as torticollis and ataxia may also be present. Upon necropsy, internal organs, especially the proventriculus, cecal tonsils, duodenum, trachea, and brain, are usually heavily hemorrhagic.

In low challenge countries, such as in North America, commercial poultry are vaccinated with lentogenic vaccine strains. These attenuated vaccines may be a reservoir or AMPV-1 but there is no evidence of reversion to virulence. Consequently, in low challenge areas, birds may be asymptomatic or exhibit only subtle respiratory signs. These conditions may worsen under suboptimal husbandry conditions, such as high stocking density, high ammonia levels, wet litter, and poor ventilation.

Despite being known for 90 years, ND continues to pose significant threats to poultry producers, both in enzootic areas and in regions or countries considered free of the disease. This situation underscores the need for better solutions, including the implementation of more effective biosecurity procedures and the availability of more efficacious vaccine solutions, if the poultry industry is to gain real control over this disease.

Understanding Newcastle Disease

Newcastle Disease (ND; Newcastle Disease symptoms) can manifest as respiratory, nervous, or intestinal symptoms in both clinical and subclinical infections.

ND can be categorized into five distinct forms:

- Viscerotropic velogenic: This is a highly pathogenic form where hemorrhagic intestinal lesions are commonly observed.

- Neurotropic velogenic: This form is characterized by high mortality, typically following respiratory and nervous signs.

- Mesogenic: This form presents with respiratory signs and occasional nervous signs, but mortality is low.

- Lentogenic or respiratory: This form manifests as a mild or subclinical respiratory infection.

- Asymptomatic: This form typically involves a subclinical enteric infection.

How does ND Spread?

Wild bird populations, as well as pigeons, backyard poultry, and small-scale farming operations, play a crucial role as reservoirs of Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV). In addition, practices such as live bird markets, cockfighting competitions, and the smuggling of domestic, zoo, or wild birds contribute to the spread of the virus. Despite limited documentation (especially for pigeons), all these populations serve as reservoirs of NDV. They are key factors in understanding the persistence, origin, and circulation of NDV. This explains why no region, country, or poultry operation can be considered risk-free.

However, it is undeniable that the primary source of the virus for healthy flocks is diseased flocks located on the same farm or nearby.

NDV is excreted from infected birds into the environment through exhaled air, respiratory discharges, and feces. It can infect susceptible chickens via aerosols or ingestion of contaminated feed or water. The virus’s relatively poor resistance in the environment underscores the importance of cleaning and disinfection.

The possibility of true vertical transmission has been debated. A few cases have been reported in scientific literature, and there have been convincing field observations. Contamination of newly hatched chicks could occur through surface-contaminated eggs, feces entering through eggshell cracks, or exposure to a contaminated environment. However, an NDV infection is known to be lethal for the embryo.

Therefore, until further clarification, it is probably wisest to follow the recommendations of the Terrestrial Code of the OIE stating that poultry hatching eggs should come from parent flocks that have been kept in an ND-free country, zone, or compartment for at least 21 days prior to, and at the time of, the collection of the eggs.

As with avian influenza, limited evidence associating natural infection with transmission in hatching eggs suggests that these OIE recommendations are adequate to prevent the international spread of NDV.

Control of Newcastle Disease

Newcastle Disease (ND) remains one of the most damaging poultry diseases, both clinically and economically but some regions or countries like Western Europe, the USA, Brazil, and others, ND has been successfully reduced and even phased out the incidence of the disease. In these low challenge areas, ND is now considered only an epizootic risk. Nevertheless, vaccination plays a significant role in the prevention program against this disease. For example, in the US, broilers are vaccinated once at the hatchery and long- lived chickens received a series of mild attenuated live priming vaccines followed by inactivated vaccine prior to the onset of egg production (link on Newcastle Disease vaccines).

Maternal antibodies could interfere with live vaccines administered at the hatchery, often to the point of complete neutralization, preventing vaccine uptake. Later exposure to lentogenic virus or circulating vaccines may contribute to respiratory tract lesions. In this context, a new generation of vaccines was needed. The vector technology with rHVT-F vaccines, such as Vectormune® ND and ULTIFEND, successfully overcome these hurdles.

Ceva Animal Health made a significant investment to understand the potential of these vectored vaccines. Scientific work, both within and outside the company, was designed, organized, and conducted in collaboration with independent research centers. The information gathered about vaccine-induced immunity and tangible protection results far exceeded our expectations.

How Does Newcastle Disease Impact Production?

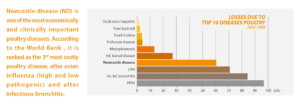

- Newcastle Disease (ND) continues to be one of the most damaging poultry diseases, with significant clinical and economic consequences.

- ND can easily complicate matters when combined with other respiratory infections such as Infectious Bronchitis.

- ND also has a zoonotic dimension. Initial exposure to infectious material can induce transient and benign conjunctivitis in humans upon close contact.

The Economic Impact on Production

In areas where Newcastle Disease (ND) is enzootic, losses attributable to this disease are commonly observed. Mortality rates can reach up to 100%, typically occurring between 21 and 28 days of age. Economic losses also encompass expenditures for extensive vaccination programs, monitoring assays, performance losses due to post-vaccination reactions, and subsequent supportive medications.

This severe economic impact is not only due to direct losses on farms (including chickens, feed, vaccines, treatments, etc.), but also to intangible costs related to the lack of birds in the slaughterhouse and subsequent broken deals with customers.

Even in countries free of the disease, flock performance losses could occur due to the post-vaccination reactions caused by live attenuated ND vaccines.

The Economic Impact on Trade

If a country, free of Newcastle Disease and consequently possessing the ‘ND free status’ necessary for exporting, is declared infected with NDV, most importing countries would immediately ban imports. For major exporting countries, this has immediate and significant consequences.

For instance, in the United States of America, a major ND outbreak occurred in commercial flocks in southern California in November 1971. During the two-year effort, 1,321 infected and exposed flocks were identified, and almost 12 million birds were destroyed. The costs associated with this operation were approximately USD 56 million. In October 2002, velogenic ND was confirmed in California, Nevada, Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico. This time, almost four million birds on 2,662 premises were depopulated, and the costs associated with the eradication efforts reached USD 160 million.

In Brazil and the USA, nearly 32% and 19% of their total chicken meat production are exported, respectively, and these two countries trade almost 70% of the world’s chicken meat. It is challenging, if not impossible, to predict the potential economic losses ND could cause in these exporting countries as they would depend on several variables such as the extent of the outbreaks, affected regions, type of birds, how quickly the disease is controlled, production costs, and many others.

Conclusion

The poultry industry is rapidly evolving, and its challenges have significantly increased over the years. For producers, efficiency has become a survival strategy rather than a differentiating point.

In today’s challenging environment, it is necessary to ‘produce more with less.’ High disease pressure, high stocking density in farms located in densely populated areas, poorly qualified workers, and the pressure to reduce the use of antibiotics are among the daily challenges faced by everyone involved in this industry. Within this context, the prevention of Newcastle Disease (ND) is just one piece of a larger puzzle.

Old solutions may not necessarily be suitable for this modern industry. Vaccines that can protect against challenges but induce extensive post-vaccination reactions and consequently cause losses in processing plants can be detrimental in an industry that operates with narrow profit margins. Even in countries or regions with very low ND field pressure, the circulation of mild live ND vaccines within or between flocks can significantly impact producers’ profitability. In this framework, the use of Vectormune® ND or ULTIFEND is extremely beneficial to producers in low-challenge areas. Replacing live attenuated vaccines with this vector vaccine reduces the circulation of lentogenic NDV strains among chickens, leading to an improvement in their performance. In high challenge areas, where ND outbreaks cause unacceptable losses, Vectormune® ND and ULTIFEND are superior to any conventional vaccine. They evade maternal antibodies, can be applied in hatcheries (i.e., well-controlled environments with well-trained workers), induce long-lasting immunity, and significantly reduces shedding. Importantly, these vectored vaccines achieve all these advantages without inducing any post-vaccination reactions.

However, even with a safe and efficacious vaccines like Vectormune® ND and ULTIFEND, it is more crucial than ever to adopt a holistic approach to the ND situation while considering the limits of biosecurity. Without a comprehensive approach, ND could to inflict enormous losses on producers for the foreseeable future.

POULTRY

POULTRY